Have you ever found yourself feeling stuck or unsure of the next step? Feeling powerless during times of rapid change can show up in many ways. Some of us go through the motions at work or home, acting out of habit or obligation but struggling to find a sense of purpose. Others shut down completely, feeling disconnected from the meaning they once found in their work or relationships. Some spring into action, asking, “What can I do?”

In the midst of uncertainty, many people are searching for ways to create meaning in their worlds and take action. Whether we realize it or not, we are looking for tangible steps to strengthen relationships in our communities and workplaces, deepen connections, and build resilience.

One of the most powerful ways to create a connected community is through a trauma-informed approach, which offers practical tools for understanding stress, trauma, and resilience–in ourselves and others. By intentionally integrating trauma-informed principles, we can create more connected and supportive environments for our teams and communities.

Since 2017, Andi and I have been guiding leaders across diverse sectors in putting trauma-informed principles into practice. It’s a simple—but not always easy—process, and we’ve had the honor of supporting incredible people as they take these steps.

Let’s meet a few of these champions who are using trauma-informed principles in practice to create lasting culture change:

Aaron Scott: Empowering Leaders with a Shared Language

Aaron Scott, North Training Manager for Burlington United Methodist Family Services, is a certified Origins facilitator for Person-Centered Trauma-Informed Care (PCTIC). After completing the train-the-trainer program with Origins, Aaron revamped his entire 9-10 day training, making PCTIC the capstone training that connects the dots among other essential staff trainings like motivational interviewing and de-escalation techniques.

The Impact:

- Unified communication: Staff now share a common framework for understanding trauma and stress.

- Stronger onboarding: New hires grasp trauma-informed principles and see how they apply across all aspects of their work.

- Cultural shift: Employees feel more aligned with each other and more confident in their approach to supporting clients

Learn more about Aaron’s approach here.

Erika Roshanravan, MD: Building Connection in Healthcare

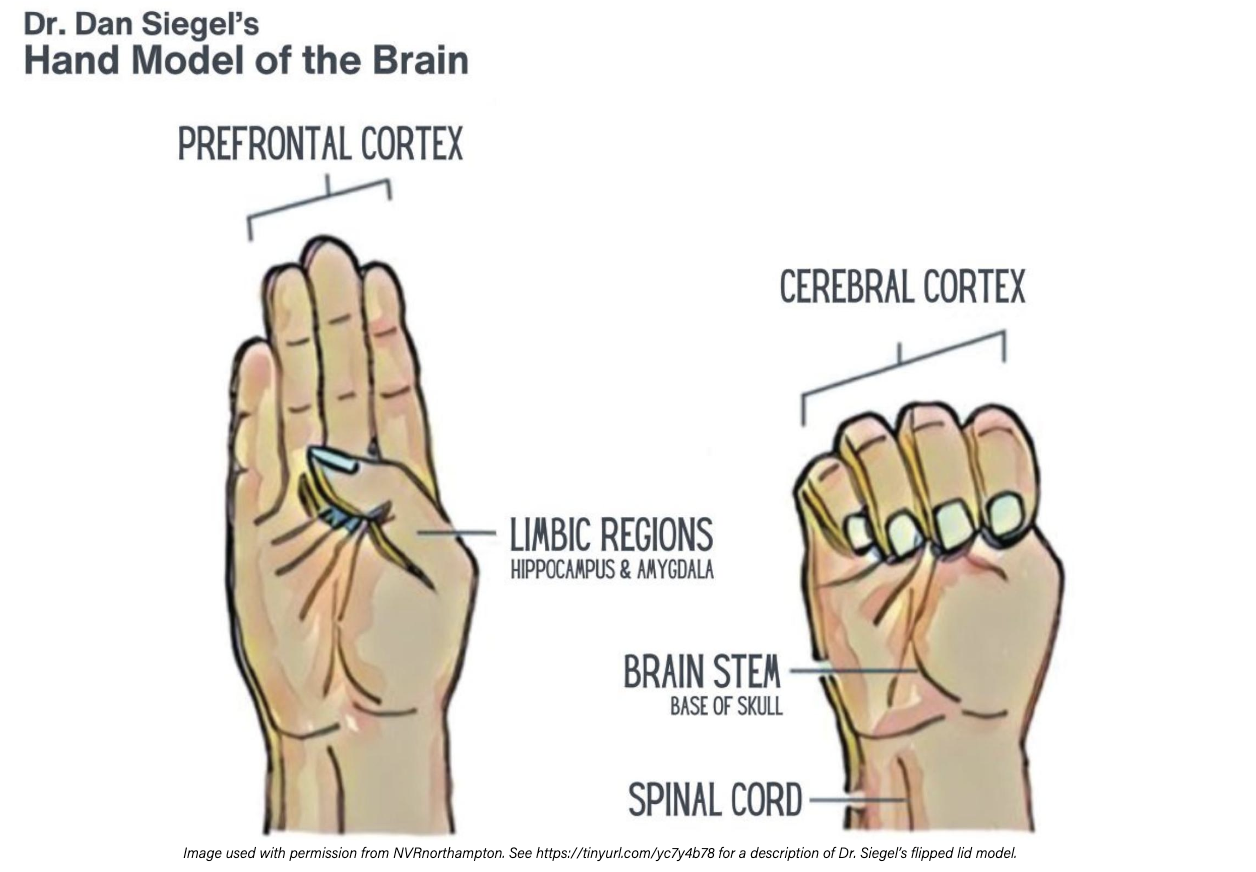

Dr. Erika Roshanravan, family physician and Medical Director at Davis Community Clinic at CommuniCare+OLE, saw an opportunity to create a stronger culture of support in her clinic. She introduced team-building activities at staff meetings, incorporating the “flipped lid” hand model developed by Dr. Dan Siegel.

The Impact:

- Open conversations: The team feels comfortable acknowledging their challenges and stress.

- Practical tools for resilience: Team members recognize the signs of stress and understand the tools to manage it—even in high-pressure situations.

- Stronger relationships: A connected culture of mutual support has taken root.

Discover more about Dr. Roshanravan’s approach and the impact it’s had on the clinic here.

Nathel Lewis, MA, BCBA: Shifting Paradigms in Special Education

As a Board Certified Behavior Analyst and the Executive Director of Children & Youth Services at Diversified Assessment & Therapy Services (DATS), Nathel Lewis leads efforts to bring trauma-informed training to his staff in West Virginia. DATS is a licensed behavior health agency that offers behavioral health services to children and youth with behavior and emotional disorders as well as children with developmental disorders. In addition to this, DATS contracts with schools in Wayne and Cabell Counties. Lewis became a certified Origins PCTIC facilitator and delivers PCTIC training, with the goal of fostering a paradigm shift. The all-staff training emphasizes one of the key principles of a trauma-informed approach: behavior is communication, often reflecting unmet needs.

The Impact:

- Confident educators: Teachers now see challenging behaviors through a trauma-informed lens.

- Stronger student support: Instead of reacting, staff can understand and address the root causes of behavior.

- Paradigm shift: A connected culture that prioritizes understanding, empathy, and connection.

Become a Resilience Champion: Join the Movement

Are you ready to bring a more connected culture to your community or organization?

Join us for the Resilience Champion Leadership Series, a 6-week, live virtual workshop designed to support leaders in developing a culture of wellness and resilience. No matter your title, this series will equip you with the tools and skills necessary to lead through a trauma-informed lens–transforming the way your organization navigates stress, trauma, and support. This training will include The Basics on Demand as a prerequisite.

USE PROMO CODE BLOGRC for $200 off The Resilience Champion Leadership Series.

Now, more than ever, we need people who can step up and lead the change we want to see. We hope you’ll join us on this journey!