By: Andi Fetzner, LPC, PsyD

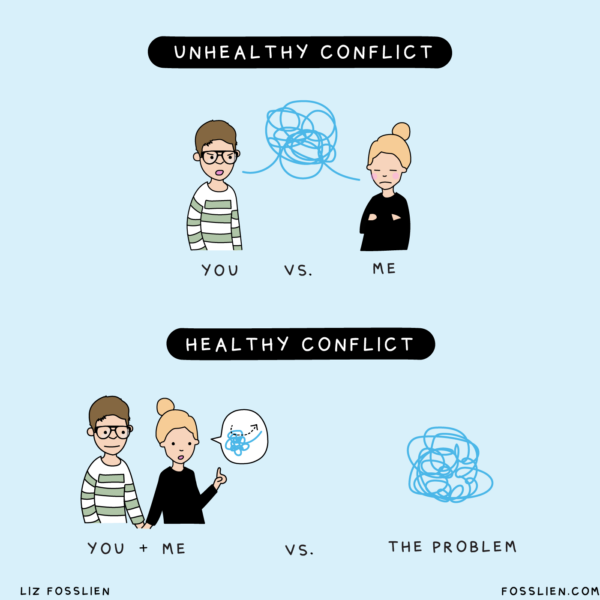

In this cartoon by Liz Fosslien, we see two contrasting images that illustrate the impact of conflict. The first shows a tangled ball of yarn between two people—one on the left and one on the right. The individuals’ expressions convey anger and sadness, emotions likely resulting from the stress of the unresolved problem. The caption labels this “unhealthy conflict.” An observer might feel a sense of competition or an urge to be “right” about the solution to the problem—though perhaps I’m projecting.

In the second image, the people are hand-in-hand on the left, while the problem is shown on the right. One person appears to be suggesting a solution, indicated by a speech bubble with an arrow cutting through the tangled yarn. Titled “healthy conflict,” this image aligns with concepts we often discuss in our work promoting a trauma-informed approach.

At Origins, we focus on supporting leaders who cultivate a culture where it’s safe to engage in healthy conflict. When we name and address stress instead of ignoring it, we take away its power. As Brene Brown (2012) notes, “When we bring stress and shame into the light, we diminish their power, as awareness and vulnerability help to counteract their influence.” Similarly, Dan Siegel (2012) reminds us that “we have to name it to tame it.” Relationships are essential in helping us manage stress. Gabor Maté (2019) describes how stress can become toxic when experienced in isolation: “When people experience stress or trauma in isolation, it often becomes toxic, as the absence of supportive relationships exacerbates the impact of adverse events.” Connection, therefore, is foundational to solving problems together.

I recently attended a Roundtable on Relational Coordination (RC) at Berkeley, where practitioners and researchers explored how relationally-based theories, methods, and practices can help address complex challenges—such as equitable healthcare, inclusive education, community well-being, climate change, and even world peace. The event took place the week of the U.S. presidential election, and the theme was “Seeing the Whole Together.” The keynote speaker on day one spoke about finding beauty in the process of our work, likening it to a chorus where each person sings their part within the group to co-create a song. The conference itself mirrored this idea, centered around connection and relationships with dynamic speakers, table discussions, and opportunities for collaboration over two days—a true “chorus” of thought and action.

Rebecca Smith, founder of The Thoughtful Clinician and a nurse midwife specializing in clinical operations, onboarding/training new clinicians, and trauma-informed care, and I were invited to present on integrating trauma-informed care (TIC) at a women’s health center (WHC) within a federally qualified health center (FQHC). Our presentation, titled Using Trauma-Informed Principles to Enhance Relational Coordination in Healthcare Workplace Operations, explored the symbiotic relationship between TIC and RC. We argued that when healthcare workers are better able to regulate their stress and work in a culture that prioritizes connection over being “right,” problems are solved in a more sustainable and efficient way. Simply put, we hypothesized that organizations with a trauma-informed culture see improved outcomes.

Let me provide a few definitions for clarity. Relational coordination is a process of communicating and relating to integrate tasks effectively. It’s shaped by organizational structures and, when strong, supports organizations in achieving desired performance outcomes—including quality, safety, efficiency, well-being, and innovation (Gittell, 2016). RC is particularly important when work is highly interdependent, uncertain, and time-constrained, such as in times of crisis or during everyday stress.

In our presentation, Smith highlighted a common interpretation of trauma-informed care—one focused on patient care. It’s about assuming patients have experienced trauma and providing care that reduces the risk of re-traumatization. She pointed out the incongruity, however, in expecting healthcare workers to provide trauma-informed care while they work within systems that are inherently stressful and often traumatizing themselves—without sufficient prioritization of workforce development and workplace culture. As she put it, “It’s not just about the patients. It’s about us too!”

In our work together at the WHC, we sought to address these barriers. The process began with a workshop that fostered small and large group interactions, where we focused on developing a shared language to discuss stress and resilience. Participants engaged in self-reflection on how stress affects their work and relationships, and we emphasized a strengths-based approach to encourage working smarter, not harder. We also identified a small group of “champions” from various clinic roles to help implement the process. Monthly mindfulness sessions and the application of TIC principles in staff and operations meetings helped reinforce this shift toward relational problem-solving. Four months later, we held a check-in to evaluate the experience, and found that TIC and RC had become intertwined, addressing both the relationships between roles and the humans in those roles.

We were unknowingly practicing many of the principles of RC while implementing TIC in the clinic.

The lesson here is clear: improving outcomes isn’t just about finding the “right” solution—it’s about building and nurturing relationships. Whether we’re addressing a tangled ball of yarn, improving quality improvement (QI) outcomes, or tackling complex systemic challenges, prioritizing connection fosters trust, collaboration, and resilience. When we shift our focus from being “right” to being relational, we create the conditions necessary for lasting solutions and sustainable change. Ultimately, RC and TIC not only support the relationships within organizations, but also provide the foundation for how we work together to overcome even the most daunting challenges.

References:

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Gotham Books.

Gittell, J. H. (2016). Transforming relationships for high performance: The power of relational coordination. Stanford University Press.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child’s developing mind. Bantam Books.